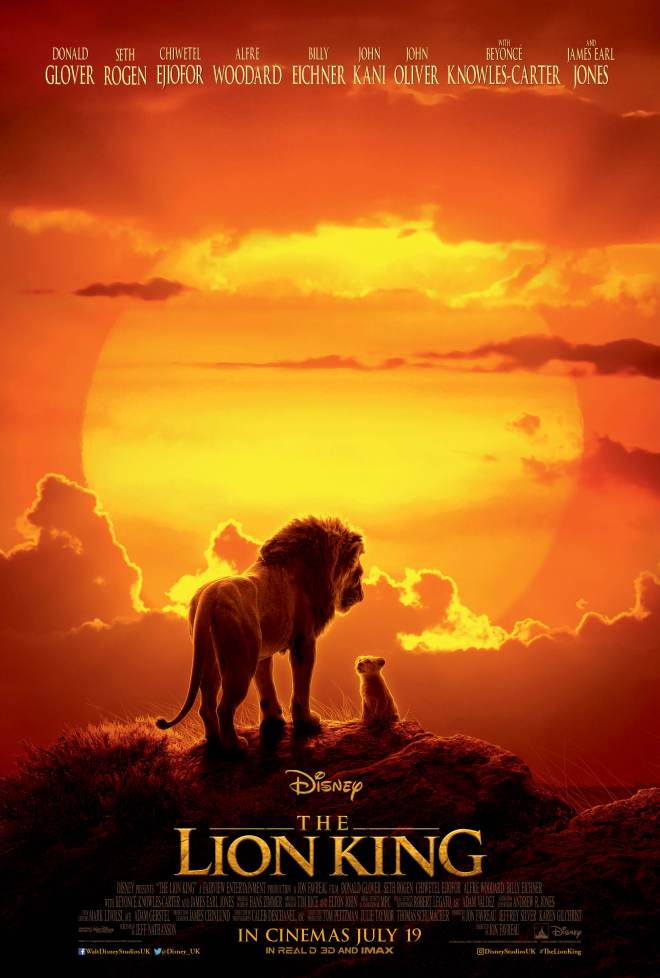

The Low-Down: For the past decade, Disney has dedicated an immense amount of resources to translating its classic animated films into live-action blockbusters – with varying degrees of success. This new incarnation of The Lion King is unusual because it is, in itself, another kind of animated film: all its creatures, great and small, are computer-generated to look photo-real. The technical wizardry on display is undoubtedly impressive. But the final film winds up undermining its own existence – what is the point of re-making something that evidently works so much better with traditional hand-drawn animation?

The Story: If you’ve seen the original 1994 film, there’ll be no surprises here. We are introduced to the adorable Simba (voiced by JD McCrary as a cub, before ageing into Donald Glover), the little prince who will one day lead his pride as a king. But even the best-laid succession plans crumble into dust when Simba’s sinister uncle, Scar (Chiwetel Ejiofor), plots against reigning king Mufasa (James Earl Jones). After tragedy strikes, Simba is forced to build a new life for himself – even though his true destiny lies far closer to home.

The Good: There’s no denying that the cutting-edge technology used to bring Simba’s pridelands to life is really quite remarkable. It’s photo-real in a way that probably wasn’t possible even a few years ago, and you’d be forgiven for thinking you’ve stumbled onto a sublimely shot nature documentary if you watch this film without the sound on. That’s not advisable, however, as director Jon Favreau clearly put some effort into engineering a new soundscape for the film. Elton John’s score is beautifully refreshed, mixed with a fresh energy and rhythm that work very well (even though the new songs – Beyonce’s Spirit and John’s end-credits number, Never Too Late – aren’t particularly memorable). The new voice cast is mostly very appealing. Glover never quite manages to slip under Simba’s skin, but Ejiofor deliciously unearths several shades of evil as Scar, and John Oliver is a hoot as fluttery hornbill advisor Zazu.

The Not-So-Good: The biggest problem with this film is that its best feature also happens to be its worst. This new kind of photo-real animation looks great, but it somehow manages to appear life-like while lacking any actual life. As it turns out, hyper-realistic lions can’t emote or talk like humans, so it borders on the ridiculous (and unnerving) to have them do just that. Moments that broke your heart in the original 1994 film might make you giggle 25 years later. It’s unfortunate, too, that Favreau’s film hews so closely to its predecessor’s script and story beats. With that crucial spark of life – or soul, as it were – already missing from these lions, you’ll only become more aware of the weaknesses that have always been a part of Simba’s rather patchy emotional trajectory. (Chiefly: does he actually learn anything? Guilt and grief alone do not a character’s growth make.)

Comic Relief: Favreau’s film almost slavishly follows its predecessor, except it allows comedians Billy Eichner and Seth Rogen a little room to riff as Timon (meerkat) and Pumbaa (warthog) respectively. Together, they provide some of the film’s funniest – as well as its most annoying – moments. In one instance, they make an inspired reference to another classic Disney movie that’s a surefire crowd-pleaser, even though its cheeky meta-textuality adds to the film’s tonal woes.

Recommended? Not particularly. This Lion King is more misfire than masterpiece.