The Low-Down: There’s a lot riding on the slim, young shoulders of everyone’s friendly neighbourhood Spider-Man. Far From Home is the first film in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) since the recent double-whammy of Avengers movies changed the status quo forever. Where does the most successful superhero franchise in the world go after this? Can non-legacy superheroes – like Spider-Man, Black Panther, Captain Marvel etc – carry on where Iron Man left off? Is the MCU running out of steam? It’s a big burden for a relatively smaller film in the franchise to carry. But Far From Home does so very well by zeroing in on what has successfully fuelled the MCU thus far: prizing character development above all to tell a story that’s as emotional as it is entertaining.

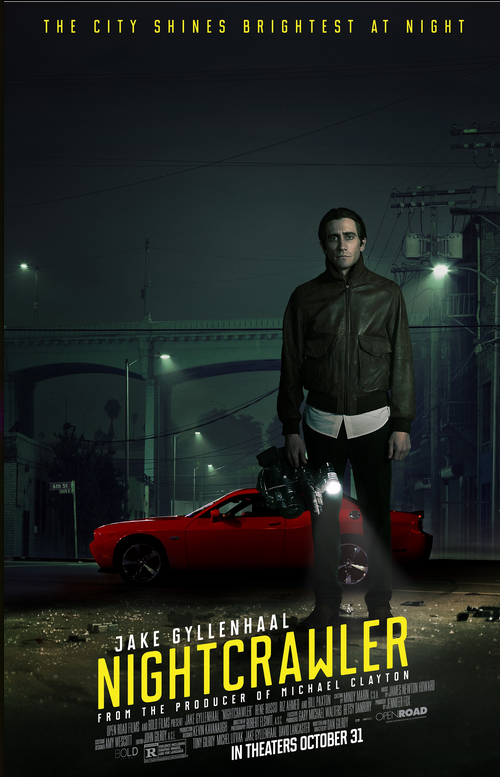

The Story: Peter Parker (Tom Holland) is trying to find his bearings in an unsettled world. He, along with half his school-mates, has suddenly reappeared on Earth – unaged and not at all dead – five years after the Snap. His mentor, Tony Stark, haunts him in the form of video tributes and street art. There’s something strange going on between Aunt May (Marisa Tomei) and Happy Hogan (Jon Favreau), Tony’s Head of Security. Amidst the uncertainty, all Peter wants is to get back to normal: to enjoy his school trip to Europe, and to let MJ (Zendaya) know how he really feels about her. But world-saving duties wait for no young man. Suddenly, Peter is roped in by Nick Fury (Samuel L. Jackson) to do battle alongside Quentin Beck a.k.a. Mysterio (Jake Gyllenhaal), taking down rogue Elementals that have already ravaged one world and are hellbent on destroying another.

The Good: At its best, Far From Home impressively blends the awkward comedy of a coming-of-age romantic drama with country-hopping superhero action thrills. It’s a delight to watch Peter use his superhuman skills as Spider-Man to navigate his way through hormonal messes of his own making – often in the same scene. This is as intriguing a narrative direction as the MCU has ever taken: using a lighter, more humorous lens to examine the aftermath of Endgame’s darker, considerably more mature themes. At the same time, Far From Home finds a rather ingenious way to quietly become one of the MCU’s most political films. (More on this later.) It’s worth noting, too, that, in a franchise filled with sublime casting coups, Holland continues to prove himself to be one of its very best. He dances nimbly through Peter’s high-school misadventures, while still tapping into the heartbroken, traumatised core of his character.

The Not-So-Good: With the action focused so squarely on Peter, his friends – especially his love interest – invariably suffer. Jacob Batalon is as goofily charming as ever as Ned, Peter’s best friend, but he might as well have the words ‘comic relief’ tattooed across his forehead. Zendaya’s sparky, sarcastic MJ – while still an interesting twist on a classic character – comes dangerously close to being a damsel in distress. And, while Jon Watts’ direction is more zippy and confident than it was on Homecoming, he doesn’t always land or weave narrative beats together very effectively. As a result, the film occasionally sags when it should soar.

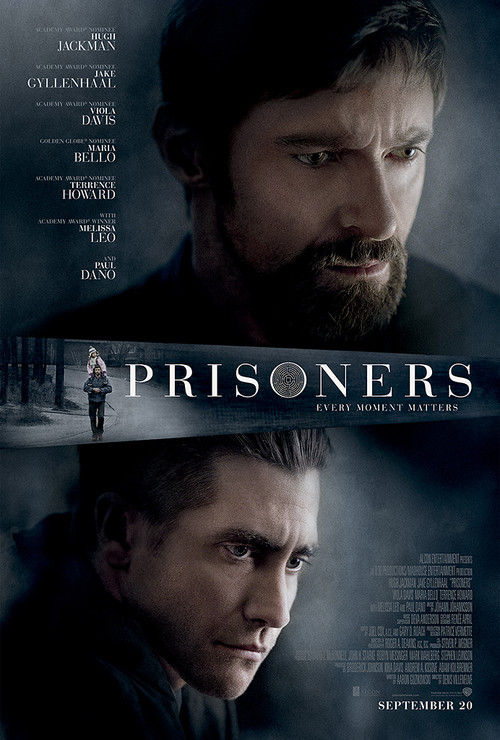

One of Life’s Great Mysterios: What is Gyllenhaal – indie movie darling and theatre thespian – doing in an MCU movie? It might seem like one of life’s great mysteries… but all will soon come clear once you realise just what drew him to the part of Quentin Beck. Fans of the comics will know that there’s far more to the character than what we saw in the trailers, but nothing will prepare them for how brilliantly he’s been reinvented for the MCU. Essentially, this is a gift of a role for the prodigiously gifted Gyllenhaal – allowing him to play every shade of hero (including a few notes of uncanny similarity to Robert Downey Jr’s Tony Stark), while also indulging his more whimsical, theatrical side. In retrospect, it’s easy to see how Gyllenhaal must have been drawn to the grim relevance of Quentin’s storyline to the world in which we live today. Just as Black Panther examined race and Captain Marvel explored toxic masculinity, Far From Home asks audiences to think about the concepts of truth and reality – at a time when both are very much under threat.

Fan Fare: Marvel has trained us all well – never leave the theatre before the credits stop rolling, for fear of missing a funny moment or a narrative nugget that hints at future films and storylines. This reaches a new level of necessity with Far From Home. Each mindblowing scene – one midway through and one at the very end of the credits – is vital to knowing (or, at least, guessing) where the MCU is going next. Also, watch out for one of Tony Stark’s beloved A.I. acronyms: it will apply, in a subversively clever way, to more than one character in the film, drawing laughs in one instance, and eliciting a deep sense of foreboding in another.

Recommended? Absolutely. There might be a few growing pains here and there, but Marvel has hit another home run – grappling effectively and emotionally with its immediate past, while raising the storytelling stakes for the future.