The Low-Down: For the past decade, Disney has been mining its treasure trove of animated classics for live-action remake fodder. Thus far, the results have been charming enough, though none of them has made a definitive case for or against telling the same story in a different medium. Aladdin has the rather dubious distinction of tilting the debate in favour of leaving well enough alone. Notwithstanding a few welcome sparks of colour and reinvention, this remake will struggle to convince anyone that it needed to exist. In fact, it provides concrete proof that – however good, however photo-real modern special effects have become – there are some things that just work better when animated.

The Story: You know the drill – Aladdin (Mena Massoud) is a street rat with a heart of gold, picking pockets to stay alive in the bustling markets of Agrabah. He’s recruited by Jafar (Marwan Kenzari) – nefarious, ambitious vizier to the Sultan (Navid Negahban) – to steal a magic lamp from the Cave of Wonders. Aladdin’s life takes a turn for the weird and wonderful when he rubs said lamp, freeing an all-powerful Genie (Will Smith) who grants him three wishes. With the Genie’s help, Aladdin makes his bid for the heart of Princess Jasmine (Naomi Scott). But romance falls by the wayside when Jafar sets his evil plans into motion.

The Good: There are some welcome efforts to update elements of Aladdin’s story to better reflect the world in which we live today. In the 1992 original, it was always frustrating that a princess with the intelligence and independent spirit of Jasmine had to find a husband to rule Agrabah. This remake doesn’t derail the romance, but it does make time to return Jasmine her agency – making clear that she’s the one in the relationship with all the (political) power. It’s a shame that Speechless, the new song she’s been given to explore her inner turmoil, feels so out-of-place in both the film and the score. The tune is disposable, presumably fished out of composer Alan Menken’s bottom drawer, with pop anthem lyrics by Benj Pasek and Justin Paul that are frustratingly generic. But hey – effort appreciated.

The Not-So-Good: Unfortunately, the rest of Aladdin never quite lives up to the spectacular heights of the original film. It’s decently made, for the most part, and the action sequences are gratifying to watch. In live action, Aladdin is something of a parkour practitioner, the camera chasing after him on his gravity-defying sprints through the streets of Agrabah. But the magic is curiously gone, bled out of scenes that should crackle with joy and emotion, like Prince Ali and A Whole New World. Apart from a couple of goofy moments that feel charmingly improvised, you won’t be able to spot director Guy Ritchie’s chaotic comic streak in the film at all. Almost all of its best bits – specifically the friendship between Aladdin and the Genie – are lifted, beat for beat, from its predecessor.

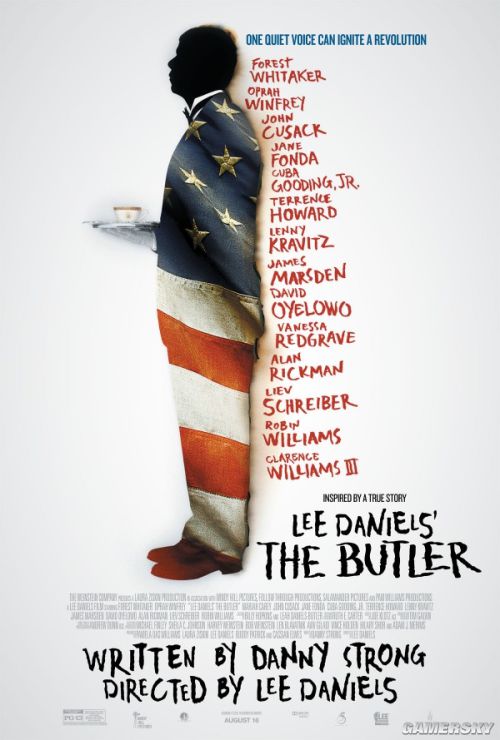

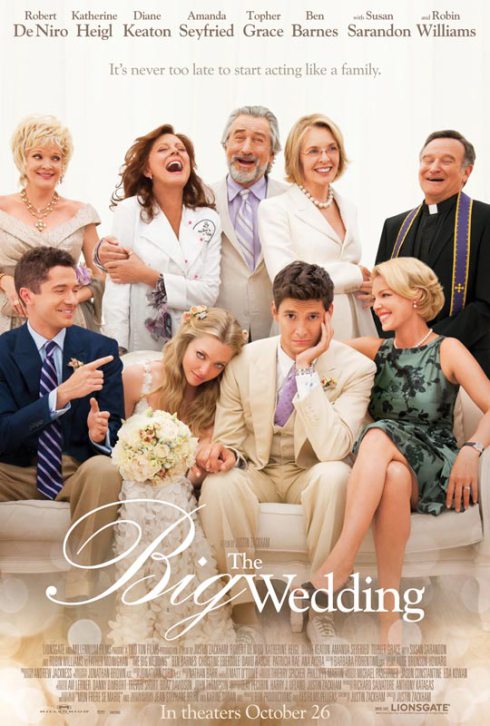

I (Don’t Want To) Dream Of Genie: Robin Williams’ Genie is one of Disney’s towering achievements – his every motion, facial expression and quicksilver transformation like lighting captured in a bottle, literally and figuratively. It’s truly one of the most sublime marriages of actor and animation ever: Robin Williams is the Genie, and the Genie is Robin Williams. It’s actually unfair to expect anyone to fill Williams’ enormous shoes, even someone like Smith, who has bucketloads of natural charisma of his own. Here, he’s not only hamstrung by having to give a performance already perfected by someone else – he’s saddled with unfortunate character design (that gigantic, puffed-up torso) and occasionally ropey CGI. As a result, Smith’s Genie becomes the stuff of nightmares. It should come as no surprise that Smith is most effective in the scenes when he isn’t big and blue. The opposite can be said of Jafar, who was made all the more sinister by his distinctively arch appearance in the animated film – something Kenzari can’t possibly hope to approximate as a real human person. At least the film’s animal companions (Abu, Rajah and Iago) are wonderfully rendered, which gives one hope for Disney’s next live-action remake, The Lion King.

Recommended? Not particularly. Aladdin tries, quite hard, but doesn’t make a convincing argument for its own existence – and occasionally threatens to ruin your childhood.