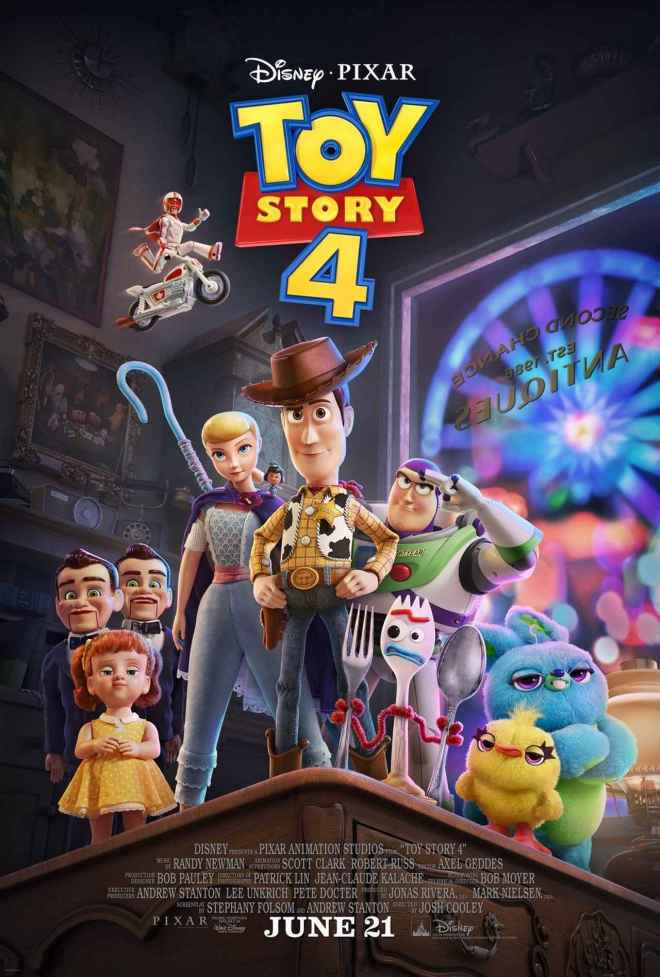

The Low-Down: 24 years ago, Pixar’s Toy Story quite literally changed the face of animation as we know it. The film presented an entirely new way of telling a story, bringing characters to life via CGI – pixels over pencils, so to speak. At the same time, Toy Story set a new high standard for storytelling in film, proving conclusively that animated movies aren’t just for kids. In the intervening decades, the franchise has even made a strong case in favour of sequels – demonstrating that they’re not necessarily soulless cash-grabs. Toy Story 4 is very much a part of that grand tradition. This is smart, soulful, sublime film-making: somehow entertaining and profound all at once.

The Story: Sheriff Woody (voiced by Tom Hanks) is trying his best to adjust to life with Bonnie (Madeleine McGraw) – the little girl who inherited Andy’s beloved childhood toys at the end of Toy Story 3. Even though he’s forgotten more often than not, Woody remains intensely focused on Bonnie and her happiness. This means going into full babysitter/bodyguard mode when Bonnie creates Forky (Tony Hale), a spork with twists of wire for hands and clumsy wooden popsicle sticks for feet. As Woody tries to keep the trash-oriented Forky safe, he’s swept into an accidental adventure – one in which he meets old friends and learns new truths about who he is and who he has yet to be.

The Great: Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Toy Story 4 is the fact that it feels like the natural, necessary final chapter of a story told in four parts. There’s no way that any of this could have been planned when Pixar first introduced us to Woody in 1995, but the progression in both narrative and character development feels utterly organic. Woody has spent the last three films grappling with his existential fear of being lost, forgotten or replaced, from his first meeting with the brash Buzz Lightyear (Tim Allen) to the day Andy outgrew him and went away to college. This film challenges Woody – and his audiences – to think hard about second chances, about changing how you look at yourself, about finding and embracing a new purpose in life. As such, Toy Story 4 might be the most philosophical movie you’ll see this year, in the best possible way.

The Not-So-Great: There actually isn’t all that much to complain about. The plot machinations can feel a little clunky at times, but Stephany Folsom and Andrew Stanton weave so much joy and humour into their screenplay that the film still zips along. As this is very much Woody’s movie, fan-favourite legacy characters like Buzz and Jessie (Joan Cusack) inevitably end up taking a back-seat. Even then, however, they each still get moments to shine. You might find yourself both thoroughly amused and mildly annoyed by the antics of Ducky (Keagan Michael-Key) and Bunny (Jordan Peele), a symbiotic pair of new characters who were clearly inserted into proceedings for comic relief.

Forking Funny: Give it up for Forky, surely the best new animated character of the year. Voiced with a bewildered tenderness by Hale, Forky is a delight – a walking, talking identity crisis created out of one little girl’s love and imagination. Even better? With his magnetic attraction to all nearby trash-cans, Forky is a fandom meme just waiting to happen. A close runner-up is daredevil stuntman Duke Caboom, who reportedly owes his ridiculously charming posing and personality to current internet darling Keanu Reeves’ commitment to the role. Toy Story 4 even manages to make its main antagonist, Gabby Gabby (Christina Hendricks), both terrifying and endearing – although there are fewer shades of grey when it comes to her ventriloquist-doll minions, led by the determinedly creepy Benson.

Cowboy Blues: Ultimately, Toy Story 4 belongs to Woody, and rightfully so. He is this franchise’s Captain America, in more ways than one. This film pays loving tribute to Woody’s big heart and unwavering, self-effacing loyalty, even as it shakes up his life and world-view when he encounters old friend and possible paramour Bo Peep (Annie Potts) again. (Bo, by the way, is now super-cool and as far away from a fragile damsel-in-distress as anyone can be.) Woody’s decisions and revelations about himself will make you weep with the most complex and bittersweet of emotions. There is joy and sorrow here, hope and heartbreak, final farewells and new beginnings, often in the same moment. In other words, it’s the stuff of life itself, and it’s glorious.

Credits Where Credits Are Due: You’ll definitely want to stay throughout the credits of the film, which are peppered with closing scenes that are essential to tying up the overarching narrative. At the very end, you’ll even be rewarded with a happy ending for one of Toy Story 4’s most minor of characters.

Recommended? In every possible way. Toy Story 4 is a masterpiece of film-making, story-telling and animation. Delightful and devastating in equal measure, it might well be the silliest and most soul-stirring film you’ll see this year.