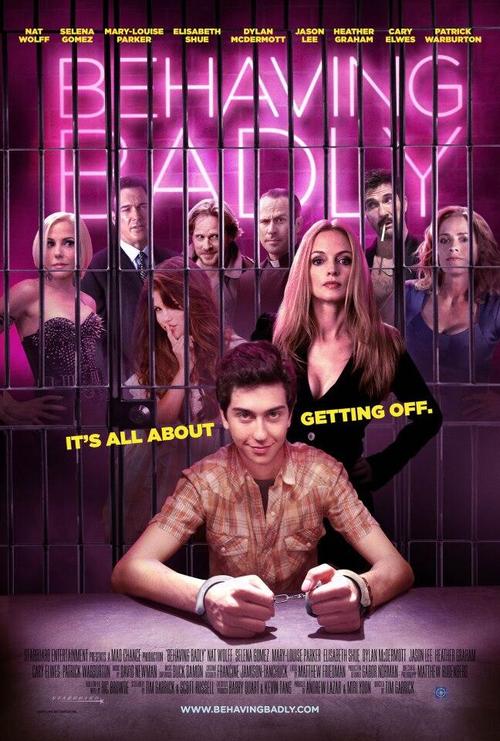

Somewhere in this tangled mess of debauchery and off-kilter, almost deliberately offensive humour is a decent movie. At its best and most promising, Behaving Badly plays like an ultra-quirky, purposefully black-hearted look at the standard coming-of-age tale we’ve seen too many times before. But it never really knows when to dial back its strange and frequently off-putting humour, resulting in a film that frustrates as much as it amuses.

Rick (Nat Wolff) is a self-absorbed, close to morally degenerate teenager growing up in a complicated household: his boozed-up mom Lucy (Mary Louise Parker) is barely coherent from day to day, and his deadbeat dad Joseph (Cary Elwes) only stays married to avoid paying alimony. Even as he navigates a huge crush on Nina (Selena Gómez), the school’s resident goody-two-shoes, he embarks on an ill-advised affair with the sexually voracious Pamela (Elisabeth Shue), mom to his strange best friend Billy (Lachlan Buchanan).

The film is every bit as complicated and filthy as its title suggests, its characters dealing in drugs, alcohol and sex with next to no moral compunction. Actually, that’s not its problem. These scenes are riddled with a grim humour, and work best when played loudly and ridiculously – as they frequently are. And so there are moments when Rick receives counselling from Saint Lola, the patron saint of aimless teenagers (played in a neat Oedipal twist by Parker); or when he must cut a deal with slimy strip-club boss Jimmy (Dylan McDermott) to score backstage passes for a Josh Groban concert. The film is almost brave in how determinedly it sinks into the most depraved of narrative depths.

But it’s hard to shake the feeling that writer-director Tim Garrick lets his own crazy creation get the best of him. He packs the film with knowing, self-aware touches – Rick frequently speaks straight to the camera, as the title character did in iconic teen flick Ferris Bueller’s Day Off – but achieves very little in the way of emotional payoff and insight. As a result, when his deliberately peculiar film heads down the road to redemption, it pretty much collapses on itself. It’s hard to believe in any of Garrick’s characters making good, when they’ve otherwise been portrayed as so horribly bad that they barely register as real human beings.

At least Garrick’s cast seems to be in on the joke. Wolff is an affable if somewhat opaque lead, largely outshone by Buchanan (delightfully weird) and the adult actors – all of whom seem to be only too pleased to have been let off the leash and told to behave, well, pretty much as badly as they like. Parker, Shue and McDermott, in particular, play the taboo-happy comedy with relish, committing so fearlessly to their parts that watching them in action becomes part of the joy of the film.

It’s unfortunate, then, that they’re doing such good work in so awkward a movie. Behaving Badly is not for the faint of heart or morally conservative, for a start. But even those who are willing to take a walk on the wild side with their teen raunch-coms will find themselves disappointed by the film, which flirts tantalisingly with the dark side but winds up being both too strange and too predictable to really work in the end.

Basically: Initially promising, this film soon feels like it’s punishing its audience – and itself – for its bad behaviour.