There are spies like James Bond – dashing, virile, sexy, with a hint of a death wish – and there are spies dreamt up by John le Carré: quiet, dark, withdrawn office-dwellers whose everyday heroism might manifest in the capture of a terrorist, or the triumph over a bureaucratic tangle. le Carré’s spies are, of course, considerably more realistic, and they prowl through A Most Wanted Man as firmly ordinary people doing truly extraordinary jobs. But, once the several layers of slick politicking and brinkmanship has been peeled away, the film’s central plot device feels almost too simple: an unexpected shimmer of light that feels out of place within the cold, sombre greys of a world lived in the shadows.

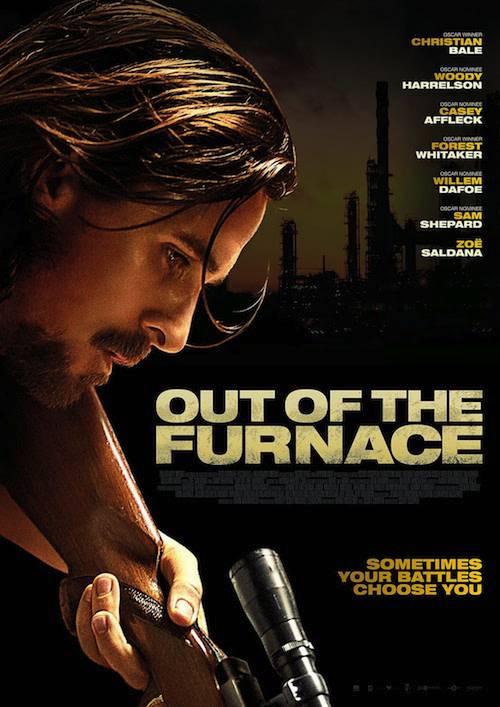

Anton Corbijn’s film shifts the focus in le Carré’s novel onto Günther Bachmann (Philip Seymour Hoffman), the head of a small espionage unit that must struggle to put forth its more radical notions on national security in the face of opposition and disdain from bigger, more hawkish agencies like the police. Everyone in the security forces sits up and takes notice when Chechen refugee Issa Karpov (Grigoriy Dobrygin) illegally enters Hamburg: Günther and his team resolve to monitor him for any terrorist links, the police just want to get him under detention, and American diplomatic attache Martha Sullivan (Robin Wright) is poised to make peace – or war – between the two camps. The situation is complicated when Issa contacts sympathetic immigration lawyer Annabel (Rachel McAdams) to lay claim to his father’s misbegotten fortune, kept within the vaults of Tommy Brue’s (Willem Dafoe) bank.

Narratives are never straightforward in le Carré’s novels, but A Most Wanted Man boasts a particularly dense and impenetrable plot – or so it seems, until everything clicks into place and it turns out that the story was almost stupefyingly simple after all. In other words, the film appears smarter than it really is, as doubt is first cast onto Issa’s motives and, later, his money. Günther is at the centre of it all – or is he? – orchestrating a surveillance operation that expands into an engagement and entrapment initiative that drags an apparently reluctant Annabel into the mix. The final act slowly unspools into something not quite worthy of its build-up: the apparently pragmatic spy, whose heart should long ago have hardened to his work and the people who surround him, is tripped up by the way people cynically operate, weighing pros and cons rather than gratitude and favours.

Fortunately, the plot really isn’t the point of A Most Wanted Man. As a study of character and relationships, it’s considerably more assured and successful. Günther, in particular, is a fascinating creation: a perfectly human, chain-smoking anti-hero toiling and skulking amidst secrets and lies, living in darkness so that others may live in the light. Corbijn paints a picture of espionage that’s at once gritty and strangely romantic, and it comes ever more sharply into focus even as its plot slowly unravels. Günther’s relationships with the women in his life are also fascinating: he shares an intimate shorthand with his deputy Irna (Nina Hoss), and a grudging suspicion of Martha borne of his past failures in the field.

The cast, led by the late and sure-to-be-sorely-missed Hoffman, is excellent, even though so many Americans have oddly been called upon to play Germans who speak entirely in English (with Germanic accents). It’s a strange choice, and some fare better at it than others (McAdams tries really hard, bless her), but it fades into the background whenever Hoffman is onscreen. A true master of his craft, Hoffman slips into the dark corners of his character to find Günther’s odd brand of humanity: a strength and conviction that should have been worn down years ago. Wright serves as a formidable ally – or adversary; her scenes with Hoffman crackle with meaning and menace, and she comfortably walks the line that allows her final scene to work as chillingly as it does.

There’s no doubt that the title of the film is meant to apply to the character of Issa: a man who is wanted, by many agencies, and for many things. But it’s arguably another sleight-of-hand move in a film filled with many small twists – the biggest and most unexpected of which is the fact that it’s actually a love letter to a certain kind of spy. In many ways, Hoffman’s Günther is that most wanted man: the wounded veteran of several wars waged in dirty, dark alleys carved out of secrets, lies and death, who somehow still sees the point of the lonely, difficult work he does. It’s a shame that the film which surrounds him doesn’t turn out to be quite as inspiring or fascinating.

Basically: Smart and searching, but better when driven by character than by plot.